For better or worse, the relentless march of technology means we’re more connected than ever, in more places than ever. For the most part that’s good. We benefit from improving communication, situational awareness, and reduced pilot workload in the cockpit. But there’s a dark side to digital connectivity, and I predict it’s only a matter of time before we start to see it in our airborne lives.

Consider the recent Heartbleed security bug, which exposed countless user’s private data to the open internet. It wasn’t the first bug and it won’t be the last. Since a good pilot is always mindful the potential exigencies of flying, it’s high time we considered how this connectivity might affect our aircraft.

Even if you’re flying an ancient VFR-only steam gauge panel, odds are good you’ve got an Android or iOS device in the cockpit. And that GPS you rely upon? Whether it’s a portable non-TSO’d unit or the latest integrated avionics suite bestowed from on high by the Gods of Glass, your database updates are undoubtedly retrieved from across the internet. Oh, the database itself can be validated through checksums and secured through encryption, but who knows what other payloads might be living on that little SD card when you insert it into the panel.

“Gee, never thought about that”, you say? You’re not alone. Even multi-billion dollar corporations felt well protected right up to the moment that they were caught flat-footed. As British journalist Misha Glenny sagely noted, there are only two types of companies: those that know they’ve been hacked, and those that don’t.

Hackers are notoriously creative, and even if your computer is secure, that doesn’t mean your refrigerator, toilet, car, or toaster is. From the New York Times:

They came in through the Chinese takeout menu.

Unable to breach the computer network at a big oil company, hackers infected with malware the online menu of a Chinese restaurant that was popular with employees. When the workers browsed the menu, they inadvertently downloaded code that gave the attackers a foothold in the business’s vast computer network.

Remember the Target hacking scandal? Hackers obtained more than 40 million credit and debit card numbers from what the company believed to be tightly secured computers. The Times article details how the attackers gained access through Target’s heating and cooling system, and notes that connectivity has transformed everything from thermostats to printers into an open door through which cyber criminals can walk with relative ease.

Popular Mechanics details more than 10 billion devices connected to the internet in an effort to make our lives easier and more efficient, but also warns us that once everything is connected, everything will be open to hacking.

During a two-week long stretch at the end of December and the beginning of January, hackers tapped into smart TVs, at least one refrigerator, and routers to send out spam. That two-week long attack is considered one of the first Internet of Things hacks, and it’s a sign of things to come.

The smart home, for instance, now includes connected thermostats, light bulbs, refrigerators, toasters, and even deadbolt locks. While it’s exciting to be able to unlock your front door remotely to let a friend in, it’s also dangerous: If the lock is connected to the same router your refrigerator uses, and if your refrigerator has lax security, hackers can enter through that weak point and get to everything else on the network—including the lock.

We can laugh at the folly of connecting a bidet or deadbolt to the internet, but let’s not imagine we aren’t equally vulnerable. Especially in the corporate/charter world, today’s airplanes often communicate with a variety of satellite and ground sources, providing diagnostic information, flight times, location data, and more. Gulfstream’s Elite cabin allows users to control window shades, temperature, lighting, and more via a wireless connection to iOS devices. In the cockpit, iPads are now standard for aeronautical charts, quick reference handbooks, aircraft and company manuals, and just about everything else that used to be printed on paper. Before certification, the FAA expressed concern about the Gulfstream G280’s susceptibility to digital attack.

But the biggest security hole for the corporate/charter types is probably the on-board wi-fi systems used by passengers in flight. Internet access used to be limited below 10,000 feet, but the FAA’s recent change on that score means it’s only a matter of time before internet access is available at all times in the cabin. And these systems are often comprised of off-the-shelf hardware, with all the attendant flaws and limitations.

Even if it’s not connected to any of the aircraft’s other systems, corporate and charter aircraft typically carry high net-worth individuals, often businessmen who work while enroute. It’s conceivable that a malicious individual could sit in their car on the public side of the airport fence and hack their way into an aircraft’s on-board wi-fi, accessing the sensitive data passengers have on their laptops without detection.

What are the trade secrets and business plans of, say, a Fortune 100 company worth? And what kind of liability would the loss of such information create for the hapless charter company who found themselves on the receiving end of such an attack? I often think about that when I’m sitting at Van Nuys or Teterboro, surrounded by billions of dollars in jet hardware.

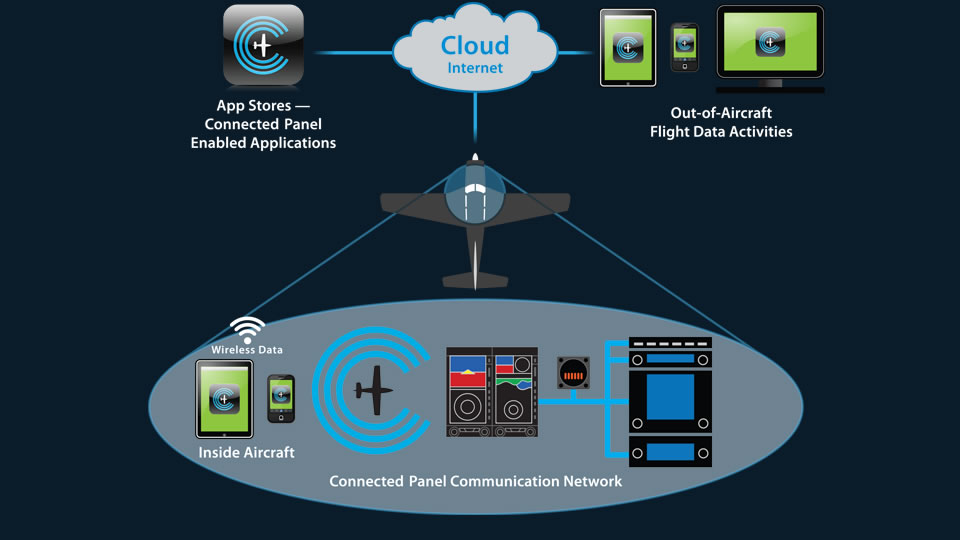

Internet connectivity is rapidly becoming available to even the smallest general aviation aircraft. Even if you’re not flying behind the latest technology from Gulfstream or Dassault, light GA airplanes still sport some cutting-edge stuff. From the Diamond TwinStar‘s Engine Control Units to the electronic ignition systems common in many Experimental aircraft to Aspen’s Connected Panel, a malicious hacker with an aviation background and sufficient talent could conceivably wreak serious havoc.

Mitigating these risks requires the same strategies we apply to every other piece of hardware in our airplanes: forethought, awareness, and a good “Plan B”. If an engine quits, for example, every pilot know how to handle it. Procedures are committed to memory and we back it up with periodic recurrent training. If primary flight instruments are lost in IMC, a smart pilot will be prepared for that eventuality.

As computers become an ever more critical and intertwined part of our flying, we must apply that same logic to our connected devices. Otherwise we risk being caught with our pants down once the gear comes up.

This article first appeared on the AOPA Opinion Leaders blog.

What an interesting and somewhat concerning bit of information. I never considered that each little thing is a potential entry point – scary indeed.

I hope that they eventually solve this issue, but I fear it’ll just be the reality we live in as we boldly march into the future.

I think you’re right, Brent. Our aircraft and aviation infrastructure are likely to become more reliant upon electronics going forward, not less. For the most part it will be a good thing, but it’ll also provide security holes which cannot be plugged with a TSA agent and a barbed wire fence.

Frankly I do not see any solution short of complete, verifyable isolation of subsystems.

A University of Texas computer programing professor is reported to have hacked a U.S. Predator drone that was working with the border patrol and briefly took command of this UAV. @aceabbott

That sounds familiar. In 2011, the Iranian military’s cyber-warfare until took control of a RQ-170 Sentinel UAV being operated by the CIA. The were able to get it to land, capture it, and reverse engineer it. And now they are manufacturing something which is basically a clone of the -170.

Our manned aircraft are becoming more and more like drones: highly computerized jets with complex systems and fly-by-wire controls.

The Target hack was through the heating/cooling CONTRACTOR, not the equipment. The baddies stole credentials from the contractor that allowed them (the bad guys) to logon to Target’s internal network. From there, they were able to access the POS (point-of-sale) terminals and imbed their nefarious software.

The contractor needed access to the network because that was how they billed Target. For all the ugly details, see this article on Brian Krebs’ security blog:

http://krebsonsecurity.com/2014/02/email-attack-on-vendor-set-up-breach-at-target/

Thanks for the clarification, Roger. Even though the contractor needed some access to Target’s system in order to facilitate billing, there’s no reason a vendor’s credentials should have allowed a hacker to obtain the credit card numbers for millions of Target customers. With WiFi connections, database updates, software upgrades, and ever more connected electronic components in our aircraft, it’s hard to imagine that something like this won’t eventually affect an airplane. For better or worse, it’s one of the side effects of the Internet of Things.

On the plus side, it should provide some employment opportunities for security experts. 🙂

And thus why we always need pilots to prevent the hacking of our planes! Click off the automation and fly!

True but what if you are in hard IMC? Gotta have those electronic gadgets to know which way to go.

One of the nice things about standby instruments is that they’re often analog. And even when they’re not, the standbys are usually simpler, less integrated, independent devices. If we are smart, we will keep them that way!

As far as being in hard IMC, even professional pilots might log 5% of their flight time as “instrument conditions”, so from a statistical standpoint, any failure would most likely be in VMC by a 20-to-1 ratio. And that would assume that a bug or hack was able to take down all the displays & sensors.

With the unique system architecture of many integrated glass panels, I certainly don’t think the total loss of all flight instruments in actual IMC is a likely scenario. But I wouldn’t say it’s impossible either. Far more likely is a hacker penetrating a COTS internet/WiFi access point on board the aircraft and gaining access to the laptop of a Fortune 500 executive.

Hmm, this is thought provoking stuff…Wish we could have hacked into MH370

<conspiracy>Who knows, maybe someone did.</conspiracy>You are such a coder at heart, Ron. Going way back to coding HTML on windows notepad. How I remember those days

I still code in Notepad! Except these days it’s likely to be a template, plugin, or CSS file than raw HTML.

You mean I can’t have my cake and eat it too? I love technology and would very much like to see a continuous improvement in EVERYONE’s quality of life. It does come at a cost, sometimes a cost greater than is immediately evident. I’ve shared this quote before and will quote it again- Teddy Roosevelt said, “The things that will destroy America are prosperity-at-any-price, peace-at-any-price, safety-first instead of duty-first, the love of soft living, and the get-rich-quick theory of life.” We need to truly understand the price of any new technology before we embrace it. I’m with Karlene, keep the pilot in the cockpit and it just might help offset some of these “costs”.

It’s almost like The Rough Rider was looking at the 21st century through a time machine, isn’t it? Electronics and automation undoubtedly ease our workload and add to safety, but as you noted, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. As one who flies an advanced tactical fighter, you’re on the leading edge of this stuff.

Test comment from Jetpack support!