Times are tough for general aviation, and we need a solid partner and advocate in Washington now more than ever. Unfortunately, the FAA is proving to be the exact opposite — a lead weight — and it’s becoming a big problem.

Complaining about the FAA has been a popular spectator sport for decades. I feel for those who work at the agency because the most of the individuals I’ve interacted with there have been pleasant and professional. They often seem as hamstrung and frustrated with the status quo as those of us on the outside. In fact, I took my commercial glider checkride with an FAA examiner from the Riverside FSDO in 2004 and consider it a model of how practical tests should be run. So I’m not suggesting we toss the baby out with the bathwater.

But somewhere, somehow, as an organization, the inexplicable policy decisions, poor execution, and awful delays in performing even the most basic functions lead one to the conclusion that the agency is beset by a bureaucratic sclerosis which is grinding the gears of progress to a rusty halt on many fronts.

Let’s look at a few examples.

Example 1: Opposite Direction Approaches Banned

If you’re not instrument-rated, the concept of flying an approach in the “wrong direction” probably seems… well, wrong. But it’s not. For decades, pilots have flown practice approaches in VFR conditions for training purposes without regard for the wind direction. There are many logical reason for doing so: variety, the availability of a specific approach type, to practice circling to a different runway for landing, and so on. John Ewing, a professional instructor based on California’s central coast, described this as “going up the down staircase”.

For reasons no one has been able to explain (and I’ve inquired with two separate FSDOs in my area), this practice is no longer allowed at towered fields. Here’s what John wrote about the change:

…the FAA has decided that opposite direction approaches into towered airports are no longer allowed. To the uninitiated, practice approaches to a runway when there’s opposite direction traffic may seem inherently dangerous, but it is something that’s been done safely at many airports for as long as anyone can remember. One example in Northern California is Sacramento Executive where all the instrument approaches are to runway 2 and 90% of the time runway 20 is in use.

At KSAC, the procedure for handling opposite direction approaches is simple and has worked well (and without incident, to my knowledge): The tower instructs the aircraft inbound on the approach to start their missed approach (usually a climbing left turn) prior to the runway threshold and any traffic departing the opposite direct turns in the other direction.

For areas like the California Central Coast, the restriction on opposite direction instrument approaches has been in place since I arrived in June and it has serious implications for instrument flight training since the ILS approaches for San Luis Obispo, Santa Maria, and Santa Barbara are likely to be opposite direction 90% of the time. For a student to train to fly an ILS in a real aircraft, you need to fly quite a distance. Same goes for instrument rating practical tests that require an ILS because the aircraft is not equipped with WAAS GPS and/or there’s no RNAV approach available with LPV minima to a DA of 250 feet or lower.

The loss of opposite-direction approaches hurts efficiency and is going to increase the time and money required for initial and recurrent instrument training. As good as simulators are, there’s no substitute for the real world, especially when it comes to things like circling to land. Between the low altitude, slow airspeed, and division of attention between instruments and exterior references required for properly executing the maneuver, circling in low weather can be one of the most challenging and potentially hazardous aspects of instrument flying. If anything, we need more opportunities to practice this. Banning opposite-direction approaches only ensures we’ll do it less.

Example 2: The Third Class Medical

Eliminating the third class medical just makes sense. I’ve covered this before, but it certainly bears repeating: glider and LSA pilots have been operating without formal medical certification for decades and there is no evidence I’m aware of to suggest they are any more prone to medical incapacitation than those of us who fly around with that coveted slip of paper in our pocket.

AOPA and EAA petitioned the government on this issue two years and nine months ago. The delay has been so egregious that the FAA Administrator had to issue a formal apology. Obviously pilots are clamoring for this, but we’re not the only ones:

Congress is getting impatient as well. In late August, 32 members of the House General Aviation Caucus sent a letter to Department of Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx urging him to expedite the review process and permit the FAA to proceed with its next step of issuing the proposal for public comment. Early in September 11 Senators, who were all co-sponsors of a bill to reform the medical process, also asked the Department of Transportation to speed up the process.

So where does the proposed rule change now? It is someplace in the maze of government. Officially it is at the Department of Transportation. Questions to DOT officials are met with no response, telling us to contact the FAA. FAA officials comment that “it is now under executive review at the DOT.â€

The rule change must also be examined by the Office of Management and Budget.

When the DOT and OMB both approve the proposal — if they do — it will be returned to the FAA, which will then put it out for public comment. The length of time for comments will probably be several months.

After these comments are considered, the FAA may or may not issue a rule change.

It occurs to me that by the time this process is done, it may have taken nearly as long as our involvement in either world war. Even then, there’s no guarantee we’ll have an acceptable outcome.

Example 3: Hangar Policy

The common sense approach would dictate that as long as you’ve got an airplane in your hangar, you should be able to keep toolboxes, workbenches, American flags, a refrigerator, a golf cart or bicycle, or anything else you like in there. But the FAA once again takes something so simple a cave man could do it and mucks it up. The fact that the FAA actually considers any stage of building an airplane to be a non-aeronautical activity defies both logic and the English language. Building is the very essence of the definition. People who’ve never even been inside an airplane could tell you that. In my mind, this hangar policy is the ultimate example of how out of touch with reality the agency has become.

Example 4: Field Approvals

These have effectively been gone from aviation for the better part of a decade. It used to be that if you wanted to add a new WhizBang 3000 radio to your airplane, a mechanic could get it approved via a relatively simple, low-cost method called a field approval. For reasons nobody has even been able to explain (probably because there is no valid explanation), it became FAA policy to stop issuing these. If you want that new radio in your airplane, you’ll have to wait until there’s an STC for it which covers your aircraft. Of course, that takes a lot longer and costs a boatload of money, if it happens at all. But the FAA doesn’t care.

Homebuilts put whatever they want into their panels and you don’t see them falling out of the sky. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

Example 5: RVSM Approvals

Just to show you that it’s not only the light GA segment that’s suffering, here’s a corporate aviation example. The ability to fly in RVSM airspace — the area between FL290 and FL410 — is very important. Being kept below FL290 is not only inefficient and bad for the environment, it also forces turbine aircraft into weather they would otherwise be able to avoid. The alternative is to fly at FL430 and above, which can mean leaving fuel and/or payload behind, or flying in a paperwork-induced coffin corner.

Unfortunately, RVSM approval requires a Letter of Authorization from the FAA. If the airplane is sold, the LOA is invalidated and the new owner has to go through the paperwork process with the FAA from step one. Even if the aircraft stays at the same airport, maintained by the same people, and flown by the same crew. If you so much as change the name of your company, the LOA is invalidated. If you sneeze or get a hangnail, they’re invalidated.

From AIN Online:

Early this year the FAA agreed to a streamlined process to handle RVSM LOA approvals, but for the operator of a Falcon 50 that is not the case. He told AIN that he has been waiting since April for an RVSM LOA.

…

Because the LOA hasn’t been approved, this operator can fly the Falcon 50 at FL290 or lower or at FL430 or above. On a hot day, a Falcon 50 struggles at FL430. “The other day ISA was +10,†he told AIN, “and we are just hanging there at 43,000 at about Mach 0.72. If we had turbulence we could have had an upset. We’re right there in the coffin corner. Somebody is going to get hurt.â€

On another recent flight in the Falcon, “There was a line of storms in front of us. We’re at FL290. They couldn’t let us climb, and I was about to declare an emergency. I’m not going to run my airplane through a hailstorm. It’s turbulent and the passengers are wondering what’s going on.â€

When forced to fly below FL290, the Falcon burns 60 percent more fuel, he said. The company’s three Hawkers have a maximum altitude of FL410, and LOA delays with those forced some flights to down to lower altitudes. “We had one trip in a Hawker before it received its RVSM LOA,†he added, “and they got the crap kicked out of them. Bobbing and weaving [to avoid thunderstorms] over Iowa, Minnesota and Nebraska in the springtime, you’re going to get your [butt] kicked.†The Hawker burns about 1,600 pph at FL370, but below FL290 the flow climbs to more than 2,000 pph.

It’s bad for safety and the FAA knows it. If they were able to process paperwork quickly, it might not be such an issue, but many operators find that it takes many months — sometimes even a year or more — to get a scrap of paper which should take a few minutes at most.

Show Me the Money

So what’s behind the all this? Americans love to throw money at a problem, so is this a budget cut issue? Perhaps the FAA is a terribly cash-starved agency that simply isn’t given the resources to do the jobs we’re asking of it.

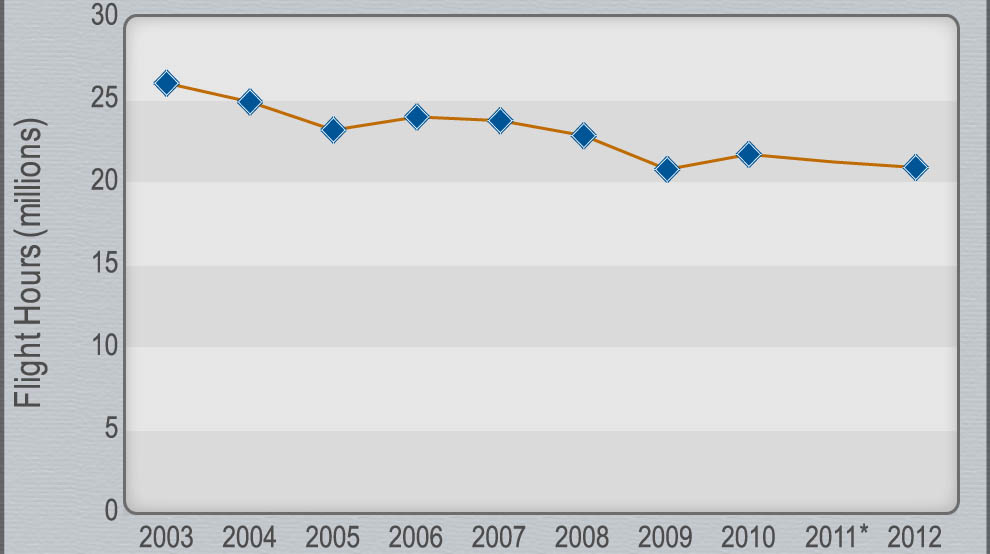

According to the Department of Transportation’s Inspector General, that’s not the case. He testified before the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure earlier this week that the FAA’s budget has been growing even as traffic declines:

The growth of the agency’s budget has been unchecked, despite the managerial failings and the changes in the marketplace. Between 1996 and 2012, the FAA’s total budget grew 95 percent, from $8.1 billion to $15.9 billion. During that same period, the agency’s air traffic operations dropped by a fifth. As a result, taxpayers are now paying the FAA nearly twice as much to do only 80 percent of the work they were doing in the 1990s.

Over that same 16-year span, the FAA’s personnel costs, including salary and benefits, skyrocketed from $3.7 billion to $7.3 billion — a 98 percent increase — even though the agency’s total number of full-time workers actually fell 4 percent during that time.

Self-Evident Solutions

Okay, we’ve all heard the litany of issues. From the inability to schedule a simple checkride to big problems with NextGen development or the ADS-B mandate, you’ve probably got your own list. The question is, how do we fix the problem?

I think the answer is already out there: less FAA oversight and more self-regulation. Look closely at GA and you’ll see that the segments which are furthest from FAA interference are the most successful. The Experimental Amateur-Built (E-AB) sector and the industry consensus standards of the Light Sport segment are two such examples. The certified world? Well many of them are still building the same airframes and engines they did 70 years ago, albeit at several times the cost.

Just as non-commercial aviation should be free of the requirement for onerous medical certification, so too should it be free of the crushing regulatory weight of the FAA. The agency would make a far better and more effective partner by limiting its focus to commercial aviation safety, promoting general aviation, and the protection and improvement of our infrastructure.

This post first appeared on the AOPA Opinion Leaders blog.

Ron,

Once again you have taken a complex topic and distilled it down to the basics using – wait for it – common sense and logic. How dare you?

Well said my friend, I couldn’t agree more!

Brent

Thanks Brent. I thought of you while writing this post, wondering how much this sort of thing hamstrings you in your work and personal flying.

Amen, Ron, amen to all you said. But unfortunately you’re preaching to the choir.

I’m not one who disrespects authority; to the contrary I normally have a great deal of respect for authority and the rule of law, but I have grown to have little respect for the FAA bureaucracy (not that they care I’m sure).

It is preaching to the choir. But it’s also helpful for those flying Part 91 to know that most other segments of the aviation industry — whether that’s UAVs, charter, airlines, E-AB — are experiencing the same thing.

The FAA is kind of a mystery. There are plenty of good, hardworking, intelligent people in their ranks. So why is the entity as a whole falling down on the job? I would imagine many of them are as frustrated about these things as we are.

My favorite is the rule that says during an emergency the PIC may suspend any rule in the interest of flight safety. I don’t think today’s FAA would allow such a thing. It just shows how bureaucratic they have become. Remember their motto: We aren’t happy until you’re not happy.

If regulations affect safety, couldn’t such a litigious society such as the US of A sue the FAA for negligence?

I don’t know. But it probably wouldn’t be an effective strategy if the goal was to effect systemic change. That sort of thing would best come from the legislative apparatus, which had the power to create the FAA and retains the power to legally change or replace it. That’s where the Congressional GA Caucus should come into play.