Aviation electronics have always been a topic of particular interest to me. For one thing, in a previous life I worked as a freelance web developer and computer programmer (read: nerd). As such, I’ve watched the evolution of general aviation avionics with great admiration for those who create them.

As a pilot, however, I have to interact with these gizmos all day long, and as an instructor must know the avionics well enough to efficiently teach them to others. This makes them a continual source of frustration because computers are supposed to make our lives easier and modern day avionics don’t always do that. From teaching Garmin’s chapter/page philosophy to learning the Honeywell FMS and SPZ-8400 systems in the Gulfstream IV, it seems I spend more time working with avionics than I do flying the airplane.

When I was at Simuflite, my G550-rated sim partner told me that the initial Gulfstream 550 training course was 33% longer than the G-IV course due solely to the complexity of the avionics. My own observation training experienced pilots to fly the Avidyne and G1000 panels is that it adds at least that much time and money to reach an instrument-proficient level.

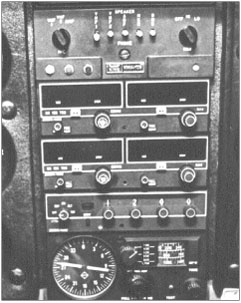

It used to be much easier. For many years, a the gold standard was silver. Silver Crown, that is — a line of digital radios manufactured by Bendix/King. Oh, there were more advanced things out there. LORAN, Omega, VOR/DME-style RNAV systems. But they were expensive and esoteric. For the most part, a decent avionics suite meant a couple of VHF com radios, a pair of VOR receivers, DME, ADF, an audio panel and a Mode C transponder. When you bought a new airplane or retrofitted an old one, that’s usually what you got. These radios were simple to operate and required no programming.

These days it’s a bit more complex. While GPS and computers have led to tremendous capabilities, it has also left us with systems which are complex enough that they can cause serious flight safety issues. “What’s it doing now?” Things wouldn’t be so bad if there were standards for the way pilots interface with the avionics, but aside from the location of essential flight data (pitch, airspeed, altitude, etc) on a Primary Flight Display, each manufacturer has their own nomenclature and operating logic for the systems they offer. The way each button, switch and knob works is different. The location of those controls varies widely.

And there are so many companies out there! Garmin, Avidyne, Aspen, Blue Mountain, Honeywell, Bendix, Becker, Chelton, Dynon, L-3, Sandel, Rockwell Collins, TruTrak, and more. These are just the ones I could think of off the top of my head.

The pace of development has increased over the past few years as hardware components have become less expensive and more capable. An AHRS which used to cost $10,000 can be purchased today for a few hundred dollars, for example. It’s led me to wonder what the “end game” in this avionics mish-mash would look like. Will one manufacturer (probably Garmin) take enough market share to force the rest of the industry to adopt it’s standards? Or perhaps some sort of avionics related safety issue will cause the FAA to step in and publish standards for avionics system interfaces?

I believe I’m starting to see an answer, and it’s due to a company which doesn’t even make avionics, and has never been involved in aviation. What are the odds of that? I’m referring, of course, to Apple and it’s iPad tablet.

I have to admit, when the iPad was first announced, I thought it would be a failure. Looking at the device, it didn’t do anything you couldn’t already do with an iPhone. In fact, it did less. It couldn’t make phone calls and at the time did not have a camera. Most importantly, it wasn’t small enough to put in your pocket, meaning it would have to be carried around in-hand everywhere you go. It was an near-iPhone with a larger screen. Who would pay for something like that?

Clearly I was wrong. Given the degree to which sales have surpassed even Apple’s initial estimates, few people had enough foresight to anticipate how the iPad would be used. I’m especially impressed by software development for the iPad because Apple uses a closed software system wherein each application must be approved by the company before it becomes available on their app store. Apple maintains tight control over the design of apps which run on their hardware. Yet this hasn’t stifled creativity and as a result the iPad is being used by physicians, librarians, teachers, and yes even pilots.

On the Gulfstream, we’ve replaced hundreds of pounds of paper charts with an iPad weighing just 1.3 pounds. Airlines are using the iPad for that same purpose with FAA blessing, something I thought I’d never see due to their reticence to accept anything not specifically certified (at tremendous expense, I might add) for aviation purposes. Part 91 Subpart K fractional operators are also using the iPad. And last but not least, owner-flown Part 91 aircraft can frequently be found with an iPad in the cockpit.

As great is the iPad is, we’re still missing a way to link it directly to the aircraft’s built-in avionics. This is vital because it’s the best way to eliminate all the data input from the programming process. For example, yesterday we made a flight from Van Nuys to Santa Monica, then on to Windsor Locks, CT and ending in Teterboro, NJ. Three legs, and each leg required a significant investment of time and effort to pick up airport information, receive a clearance, and program that flight plan into the avionics.

The duplication of effort could easily be eliminated. A computer at Arinc came up with a flight plan for us. Then it was filed with the FAA, whose computer system came up with an acceptable route based on that filing. That route was read to us verbally over a radio and manually programmed into a computer on the aircraft by me. Why not simply beam the data to a device like an iPad, which pilots could verify before zapping it to the avionics? It would have easily saved an hour of time yesterday. Time is money. Do the math.

You’d think the answer would come from the FAA or the airlines, as they would have the most to gain from increased efficiency and safety such a system would provide. Instead it’s coming from the bottom up. I don’t just mean general aviation, but specifically experimental GA. AVweb posted this video demonstrating the Aspen Avionics’ Connected Cockpit:

The Aspen rep explains it far better than I could. “A way to connect personal devices with the certified avionics installed in the aircraft”. Ideally this will be a two-way communication link, allowing you to download transfer essential flight data like block times, fuel burned, distance traveled, ground track, etc. back to the tablet for use in filling out logbooks, trip sheets, tracking maintenance requirements, and generally leaving the pilots free to aviate instead of program computers and complete paperwork.

Once we have that link and the programming has been eliminated, we’re on easy street because people will be able to bring a personal device like an iPad (which they already know how to use) and a software package they’re comfortable with (ForeFlight comes to mind) and communicate with whatever may be installed in the aircraft. Aspen Avionics gets that, and I believe their Connected Cockpit is just the beginning of The Great Integration. It can’t get here soon enough.

I agree – the iPad is revolutionary for the cockpit – in Aus we have some amazing new apps available including moving maps on Aust charts for the first time on any avionics system for an incredibly cheap price.

I’ve never seen such incredible advancement in aviation tech in such a short time – it is truly staggering.