It’s mid-afternoon on The Day After, and I’m sitting in my suite looking at a coffee table. There’s nothing on it. Likewise, the bed, floor, nightstands, granite counter tops — come to think of it, the entire hotel room — sits completely devoid of the books, class notes, reference manuals, fold-out diagrams, flow charts, cheat sheets, and Post-It notes which have polluted the joint for more than three weeks. Lord knows how the housekeeping staff managed to clean anything with so much detritus scattered all over the place, but they did it.

And now it’s all gone.

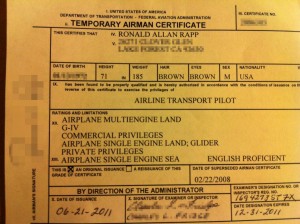

In it’s place rests a single 4-inch square piece of paper, a Temporary Airman Certificate. It’s exactly the same as the old one with the exception of six new letters: “ATP” and “G-IV”. Six letters! Is is possible that all the time, effort, and money applied to this crazy adventure can be reflected with only six measly letters?

If you’re a pilot, hell yes. I keep looking at the certificate and thinking about how much I’ve learned, and how much is still to be learned about the Gulfstream IV. It’s probable that the former outweighs the latter by a ratio which is embarrassing to admit to oneself. Still, I’ll take it.

Rewinding the clock 30 hours (though it seems more like 30 days) finds me and my trusty sim partner rolling into room 333 at Simuflite for the start of our checkride. The adventure began at 10:30 a.m. and didn’t finish until nearly 9:30 p.m. Eleven hours! That seems inordinately long, but when you think about it, a typical checkride for a private or commercial certificate is probably five hours long, and since both me and my sim partner were having our checkrides at the same time, it ought to take twice as long because we have to do everything twice.

What neither of us anticipated was that it would feel a lot longer even than that. A product of test anxiety, not to mention the end of more than three weeks of living out of a suitcase and a flight manual, I expect.

Our examiner, Tod, had been our instructor for a significant chunk of the ground school. We knew he was a good guy, but we weren’t too sure how he’d be during a checkride. When someone takes off their instructor hat and puts on the examiner hat, what do you get? The answer is: it varies. Teaching is technically verboten during a checkride, and examiners are acutely aware that they’re the last threshold to be crossed before the students are authorized to go out into the real world with that 75,000 pound chunk of metal and fly it across the planet at darn near the speed of sound.

The oral portion of the test was surprisingly easy. The questioning was thorough but fair, and for an hour and a half we answered everything to Tod’s satisfaction. I did mangle the answer to a question about when the auxiliary pump would activate during a specific kind of hydraulic system malfunction, but he let it go. Likewise, my sim partner got one wrong as well. It was a question whose answer was so obvious that you didn’t even think about it from that perspective.

We — or should I say, I — was given a weight & balance scenario to complete, along with a few performance calculations. My sim partner is already type rated on the G-IV, so he wasn’t required to partake. Of course, he didn’t know that going in, and had spent the morning doing weight & balance computations in preparation. Murphy’s Law. Tod told him he could take a break while I worked on the performance data packet, but being the good guy that he is, he stuck around and provided moral support while I crunched all the numbers. To be honest, it’s simple stuff once you know where to look for the data.

We were given a half hour to grab a bite, and then it was off to the briefing room to prepare for the simulator flight. I think we both wanted to fly first, but my sim partner was gracious enough to allow me to have first crack at it. We both knew whoever flew last would be awfully tired by the end, and that could lead to a stupid mistake and a checkride failure. I was willing to let him to first, but in the end Tod said I should go first because I was undergoing a more high-profile test.

Tod laid out the approach plates and the checkride scenario. It was a profile we had been well prepared for: start with a cold, dark airplane and do everything necessary to get it up and running. Then, a 500′ RVR low-visibility taxi from the ramp to runway 32 at Anchorage, followed by the Anchorage Four departure procedure, V334 to Kenai, then back to the PANC. In between, we had stalls, steep turns, and unusual attitudes.

About those steep turns. They really had both of us nervous. A single degree of pitch movement will quickly turn into a 100′ altitude loss or gain when you’re flying at 250 KIAS at 11,000′. The G-IV handles like a truck, and rolling from a left turn into a right one requires serious muscle to hold the pitch attitude steady. Most of our steep turns had been fine, but every now and then we’d flirt with the 100′ altitude or 10 knots airspeed change limits, not something which engenders a warm-and-fuzzy feeling.

The testing standards are fairly generous and not difficult to hold to, but the consequences of exceeding them for even a moment could be severe, especially for me. As the one undergoing an ATP certificate and G-IV initial type rating checkride, I was told there wasn’t to be any leeway. My sim partner was receiving a more routine Part 135 check, and as I understand it, even though he was to be held to the same standards for his flying, a minor amount of remedial instruction was allowable on his portion of the test. As it turns out, neither of us needed any freebies, but those steep turns can go bad quickly.

After the airwork, the cockpit filled with the bong-bong-bong and various warning annunciator lights of a Major Problem as the left engine summarily rolled back to zero thrust. I ordered an immediate airstart, and we got the engine back online within a minute. Then it was vectors back into town for the RNAV 7R approach, which I hand-flew to LNAV/VNAV minimums without breaking out of the clouds, so we executed the missed approach and held as published. We returned for the coupled localizer/DME approach to runway 7R and circled to runway 32.

A low-visibility circling approach in a Category D airplane is nothing to sniff at. Most airlines don’t even allow them unless the weather is VFR. What makes this particular approach challenging is the hill northeast of the airport. This terrain rise gives the impression of a high descent rate during the base-to-final turn. If you ease off on the descent, however, you’ll end up too high and either end up back the soup, exceed the descent rate limits, or land too far down the runway to meet the test standards. In addition, the simulator doesn’t have 360 degree visuals. I’d say they’re more like 180 degrees — excellent by any standard, but still less than you’d have in an actual airplane. But I’d worked on the approach over the past two days and nailed it. In fact, it was the thing I was least worried about on the checkride. I could do that approach a hundred times in a row and grease it onto the touchdown zone smoothly every single time.

After landing, we turned around and departed runway 14, aborting at about 50 knots for an uncommanded thrust reverser deployment. After Tod cleared that fault, we taxied to the end of the runway and departed on 32. At V1, the left engine failed and I flew the ILS 7R approach on a single engine, followed by the single engine missed approach and a second engine-out ILS to a landing.

The last item on the checkride was a no-flap landing made from the right seat. Technically all that was required was a takeoff and landing from the right seat, but for expediency we combined it with the no-flap.

By this point we were both wiped out… and my sim partner had yet to even start his flight test. As I noted previously, my nightmare scenario wasn’t busting my checkride, it was causing my sim partner to bust his. There are a hundred ways to do it, from distracting him to setting up the FMS incorrectly. I’m proud to say that despite being tired enough that I couldn’t tell right from left, I held up my part of the bargain and we both finished with what Tod described as “an impressive performance” and one of the best he’d seen from an initial candidate. We shut down by the checklist and exchanged handshakes after mustering the strength to drag ourselves out of the simulator. We were done!

The debriefing was mercifully short, basically an exchange of paperwork and the receipt of my temporary certificate. Speaking of which, one of the guys in my class told me that some countries will not allow a pilot to fly on a temporary in their airspace. That seems absurd to me. The FAA can take as long as 120 days to send out a permanent certificate. Are international pilots supposed to simply not work until that time? I suppose I’ll find out when my next bit of training beings. Oh yes, the training never ends when you’re a professional pilot. There’s Part 135 indoc, international procedures course, RVSM training, the list goes on. And on. And on. And there’s a five day recurrent training class required on the jet every six months to stay current.

Those are things to worry about tomorrow, though. Now is a time to relax and enjoy what I’ve achieved. Oh, and I almost forgot, there was more good news last night: each of our classmates passed their tests, and better yet, a student of mine back home who was taking his private pilot checkride also passed. That last one really took a load off my mind, and as a result I left Simuflite for a final time — until recurrent training is due in six months, at least — a very relieved and happy guy.

Now that the course is complete, I look back on the description of a turbojet PIC type rating as “drinking from a fire hose” as an apt one. They throw a lot of information at you, no doubt about it. But that’s a minor point. How well you’ll do in a course like this is determined as much by personality traits as anything else. Do you have the discipline to study, yet the wisdom to take time off so you don’t melt down? I can’t tell you how many times I was advised by Simuflite instructors not to study on a day off. Can you handle the stresses of a course like this, roll with the punches, accept the disparate personalities of your sim partner, instructors, and classmates? If you can’t, it will interfere with your learning, believe me. Can you function under the stresses inherent in such a course? The pressures experienced in training are not severe, but they are constant. And they’ll be upon you for three straight weeks.

From a experiential standpoint, this course should be quite manageable, even for someone without any pre-existing type ratings, assuming you come to school with well-developed instrument skills and sufficient real-world flying experience. Two of the five guys in my class came in with no type ratings, and both of us did just fine.

My years working as an instrument instructor and the thousands of hours of hand-flying BE-90s and aerobatics provided the foundation, the skills which were so useful during G-IV training. That’s why I urge flight instructors, banner towers, Medfly pilots, and others in so-called “beginning” flying jobs to focus on their current gig. You’re gaining the skills and experience which will get you through training when you land that dream job.

In fact, when compared to the accelerated CFI course I survived in Las Vegas seven years ago, the G-IV Initial was easy. In Vegas, the days were 15-16 hours long, I was living in a lousy hotel, and there was no sim partner to lean on or commiserate with.

As with the CFI course, the key to picking up a new airplane is to have transitioned to many new ones over the years. If you’ve flown the same aircraft for 20 years, learning a new one will be tough. But if you’re constantly moving back and forth between a King Air, Pitts, Cirrus, RV-6, etc. then you’re used to adjusting quickly to a new cockpit. Just one guy’s thoughts on the matter…

So. My initial training on the G-IV is complete. Now, as they say, the real learning begins. I expect I won’t be comfortable in the plane for quite a while. That’s normal. In the meantime, my bags are packed and it’s time to get caught up with the wife and the life I lead outside the cockpit.

Congrats. Frankly, I had almost deleted the feed from this blog as it had been a while since you had posted. After reading the series on the G-IV class I am glad that I did not.

Hopefully you have something lined up to put that type rating to use. As one of my former instructors used to say, it’s always better to have an employer pay for a type rating than you. Of course, that was in the old days before the “new economy”.

Either way, good luck. Try and find a way to keep posting.

Thanks for the posts.

Joseph–

I certainly understand about deleting the feed. I’ve actually wondered whether it was worth keeping the blog around myself. Nothing worse than a site with perpetually outdated stuff. New content is king.

It can be tough to post regularly, as I try for quality over quantity and there’s not as much free time as there used to be in my life. But it’s an enjoyable avocation and one I will try to continue.

Thanks for sticking with me 🙂

Congratulations on getting your G-IV rating and thanks for enjoyable series of articles. I’m not a pilot (yet) but I enjoyed reading about your adventures and the process of getting the rating

Thanks David! Glad you found the series worthwhile…

What’s more fun to fly the GIV or the Pitts?

It’s hard to even compare the two. For fun, I’d have to say the Pitts. The plane was designed with fun in mind… and nothing else. The Gulfstream is designed to travel long distances with extreme comfort, utility, and speed. And it does all that every bit as well as well as the Pitts does aerobatics.

The two are at opposite ends of the spectrum, but one thing they have in common is that they’re both top-of-class. I met a Southwest pilot yesterday who flew F-14s and F-18s in the Navy, and even he thought of the Pitts as the ultimate embodiment of fun.

Excellent! Big congrats!

Congratulations, Ron! And thanks for taking the time to write extensively about it; no doubt that doing so took a lot of time—something it doesn’t seem like you had in excess over the past few weeks.

Glad you enjoyed the writing, Ty! It does take some time to pen the entries, but I find it somewhat therapeutic. It takes my mind off technical stuff or other minutia I’m attempting to memorize. And lets me focus on the larger picture, the overall experience of the program. I’d always wondered how it compared to other types of GA training with which I was familiar.

I believe the 6-month recurrent will introduce a bunch of new stuff. For example, I never did an emergency gear extension. I know *how* to do it, but we never actually did it in the course of training.

Still a tremendous amount to learn…

Enjoyed reading your final review. All I can say is WOW. I didn’t realize you were getting your ATP as well. What a HUGE undertaking spanning 3 weeks. I remember how stressed I felt for my PPL Checkride… and after reading your blog feel quite humbled! So again… a huge congratulations! Hats off to you!

Thanks Dorian! Yes, it was quite a chunk to bite off, but I enjoyed the experience and met some great people along the way as well.

The private checkride can be very stressful. I think a large part of that is the “unknown”. As it’s your first aviation checkride, you aren’t sure exactly how it all works. Once you’ve taken a few checkrides, you start to get comfortable with the actual testing process and procedures. That’s my theory on it, anyway. 🙂