A friend was searching far and wide for a ï¬rst officer to fly an exquisite Falcon 2000EX EASy, but couldn’t ï¬ll the position despite the six-ï¬gure starting salary accompanying it. The company had advertised, offered hefty referral fees, upped the salary and beneï¬ts package—and still came up empty-handed.

I’d sent him pilots for other jobs in the past, but by this time my own cupboard was bare. Everyone I knew who was even remotely qualiï¬ed for this kind of gig was already fully employed.

How We Got Here

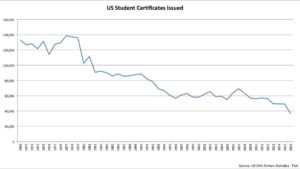

This conundrum started many years ago. Sometimes it feels like it was in a galaxy far, far away, too. It cost me $4,000 to earn a private pilot certificate in 1998. Can you imagine? That same certificate at the same FBO will set you back four times as much today. Higher fuel prices, insurance rates, maintenance and parts prices, and a shrinking industry ratchet up the costs for those who remain. Some are forced out of the game altogether, while others never get a chance to start.

We’re all familiar with the downsizing, mergers, furloughs, and bankruptcies that rippled throughout the aviation world after 2001. Flying careers had already lost much of their luster and accessibility even before the walls closed in post-September 11.

Ironically, this mid-2009 timeframe was almost the exact moment the mandatory retirement age for airline pilots was raised to 65. This effectively masked the avalanche of Part 121 retirements for another half decade. And while the existing pilot workforce was growing older, there were precious few people training to replace them. The chasm was growing right before our eyes, but most were not sage enough to recognize what was happening—rumors of pilot shortages have been a part of almost every decade since the Wrights invented the airplane.

Business Aviation vs. The Airlines

While the major airlines seem to be holding their own when it comes to recruitment, they’re doing so largely at the expense of business aviation and regional airlines. Christopher Broyhill wrote in December’s Business Aviation Advisor that the majors used to rely on the military for a steady supply of aviators, but now “target business aviation pilots, because they have time in sophisticated aircraft and are a known commodity when it comes to training and upgrade.â€

This labor shortage may prove far more challenging to solve than even the industry itself has realized, because the skill set required of business aviation pilots extends far beyond that required of an airline pilot.

Airlines ply a limited route network, whereas business aviation can take you anywhere on the planet, and requires corporate and charter pilots to operate with greater autonomy and less support. My company’s director of operations once called to alert me about a trip to Pyongyang. (That flight was canceled, but during the planning stages I was surprised to ï¬nd that Jeppesen does include charts and data for North Korea. That would’ve really given me a leg up when comparing destinations with other Gulfstream pilots.)

Business aviators must function at various times as flight attendants, managers, dispatchers,

instructors, mentors, recruiters, businessmen, accountants, and more. Some employers run steady and predictable schedules, but for most, the only constant is change. And let’s face it, not everyone thrives in that environment. Many ï¬ne aviators lack the requisite skills, or simply have no interest in these sorts of challenges. Some of the talents are innate and cannot be taught—you either possess them or you don’t.

The charter industry has a unique challenge in the form of requirements from safety auditing ï¬rms such as ARG/US and Wyvern, which are ubiquitous components of the competitive Part 135 landscape. These auditors set standards that far exceed FAA minimums. This can have positive safety repercussions, but it may also reduce the pool of available candidates.

Solving The Problem

Will Rogers once said, “If you ï¬nd yourself in a hole, stop digging.†Doctors have the same philosophy: First, do no harm. In aviation terms, that means retaining existing pilots by providing compensation and quality of life that meet or exceed what others are offering. While that sounds pricey—and it is—it’s almost certainly less expensive than replacing high-quality flight crew.

Second, since pilots require years of training and seasoning in order to qualify for corporate aviation or airline jobs, the critical role general aviation plays in the health of our industry has to be acknowledged. Light GA is the foundation of the proverbial food pyramid, providing the experience and opportunities necessary for building a well-rounded aviator, and it must be respected and nurtured if the rest of the aviation world is to thrive.

Achieving that goal will demand a reduction in the cost of light GA flying. This is one area where a modicum of progress can be seen: the Part 23 rewrite, a shift away from heavy-handed FAA enforcement policy, the availability of non-TSO avionics for the light GA fleet, and so on. But more must be done. Liability and tort reform would be an excellent place to start. Access to reasonable ï¬nancing options are another “must have†element of a healthy aviation ecosystem.

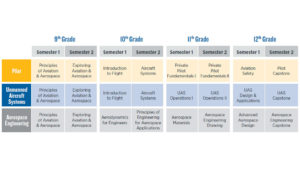

We’ve got to expose kids (and parents) to the wonder of general aviation at an early age, getting them out to the airport, bringing aviation-related STEM activity into their classrooms, and making airï¬elds a hospitable place for visitors again.

I know from ï¬rsthand experience what an outsized impact these accessibility efforts can have. In 1977, a kind TWA flight engineer spent a few minutes with me after a flight to St. Louis; I’m sure he forgot about the experience shortly thereafter. I didn’t. Four decades later it remains an indelible and cherished memory. It’s also part of why I’m an international captain on a large-cabin Gulfstream today.

Fixing the industry’s employment shortfall is possible, but it won’t be easy—or cheap. The market has turned, and the future belongs to those who embrace the change.

This article first appeared in the April, 2018 edition of AOPA Pilot Turbine Edition

As a former business aviation pilot who left for the Airlines I can say… The water is nice, come on over! The worst of the Airlines (reserve) is better than the best business aviation job I’ve seen. On call 14 hours a day 18 days a month is a lot better than on call 24/7 with 4 hard days off, rarely of your choosing. With the rate of hire at the Airlines I only did two months of reserve and had over 10% of our pilot group behind me after the first year for a nice pad against furlough. For my friends like Ron with good business jet jobs I certainly hope this has led to higher pay and more time off. However, I fear that this shortage is only going to net higher pay which, for many, isn’t the priority.

I think you’re right, Ty: more pay is being offered, but not necessarily a better quality of life. I’ve got friends making $300k or more, but they work hard for the money. Quality of life is an area where large scheduled airlines have a significant advantage over most business aviation jobs. There are quite a few 91 jobs where life is pretty sweet, but those are like Easter eggs — hard to find.

If retention of high quality employees is a primary goal for the business aviation community, the quality of life issue will eventually rear its head.

51 years old, worked as a CFI for not quite 2 years, ~1300 hours TT, left aviation in 2004. Corporate and airline friends have had their struggles but now are doing well and tell me “come on in, the water’s fine!” Tempting, but with what it would cost in terms of time and money to get qualified (hours, currency, additional experience), and knowing it could all go belly up again, I don’t think I have the stomach for that. Or am I looking at this as “glass half-empty?”

I don’t know if I’d describe it as “glass half empty”. More like “burned once, twice shy”. While I agree with your corporate and airline friends that it’s a pilot’s market and there are plenty of jobs, I’d also have to admit that your perspective is an entirely reasonable one. If a major war breaks out somewhere, a 9/11 type event occurs, or the economy takes a 2008-ish downturn, things could change quite rapidly. I’m always thinking about stuff like that. It’s one of the reasons I keep my debt low, savings high, and stay in touch with old colleagues as though I was going to be hunting for a job soon. Because you just never know.

Of course, that all holds true no matter what field you work in. For me, life’s too short to spend the day doing something I dislike. That’s why I work in this business.

But the calculus is different for each of us.

I don’t think that obsessing with women pilots buys us much. I went through these futile efforts in computer technology and it all comes down to girls simply not interested. In USSR, women engineers were numerous, close to 30%. But it happened because of hardships. They were numerous in construction, too. As soon as you let them have it easy, they find easier things to do. Piloting may be not as dusty as construction, but it’s not particularly easy wrt. the preferred lifestyle. Bottom line: you can only get 50% of women pilots if you institute quota programs, and when you do, their quality will be a step below (not because women are incapable, but because of the necessary dual standards embedded into quotas).

Interesting data point regarding the IT and engineering industries. I didn’t mean to suggest we’d reach a 50/50 parity between the sexes. Some jobs simply have more of one gender than another. Nurses, teachers, pilots, etc.

I don’t think quotas are the answer either. We need ideas and policies which boost airmanship quality rather than place it on the back burner in favor of demographics.

With women representing only about 5% of the workforce, even a slight increase (to, say, 10%) would be a definite assist in helping stave off the personnel shortage. The nice thing about these STEM-focused curriculums is that they open the eyes of young men and women to all sorts of technical jobs, not just those in the cockpit.

Hi Ron! Great article as usual. I tried emailing you but I think rapp.org isn’t working 🙁 Any other email I can try you on?

Glad you enjoyed it, Graeme. Yes, my ISP is upgrading their email capabilities… although thus far it’s not been much of an “upgrade”. My email account’s been broken for 3 days now. In the meantime you can reach me at my Gmail account. It’s “ronrapp” @….

Interesting article, as always. I do have to say, I earned my PPL in 1978 at under $1000 (at SNA). Can you imagine?

My primary CFI pushed me toward an aviation career, but even at 17 it seemed to me a fickle industry…I went into engineering and it’s been a rewarding career. But, every so often, I wonder how it might have turned out if I’d pursued aviation as a vocation rather than an avocation.

I most certainly enjoy your posts vicariously!

$1,000 is 1978 sounds about right. With inflation being as high as it was in the late 70s and early 80s, it doesn’t surprise me that it would have risen to $4,000 by 1998. Just for kicks I put it into an inflation calculator and that $1,000 was worth nearly $2,600 by 1998.

But for that certificate to cost $20,000 by 2018 with the very low inflation we’ve had over the past two decades? The same inflation calculator says it should be about $3,950.

Your decision to bypass aviation as a career for a more stable field puts you in good company. Many others have told me similar stories. And it’s entirely understandable — logical, even. Because any time you take a passion and make it a vocation, you run the risk of turning the thing you love into something you don’t. They call it “work” for a reason, right? 🙂 I guess you’ll never know what might have been, but you certainly did miss out on some very turbulent years in the industry. Maybe you’d have been with the right airline and had the seniority to avoid major career disruption… but maybe not.

Thanks for the kind words about the post. Glad to have you as a reader!

Ron, I must be the exception. I have no desire to pursue an airline career. In fact, my goal is to be a 135 career Pilot. My goal is to fly the PC-12 professionally. I am a former Air Traffic Controller, who realized I would rather be looking out the window at the horizon, than at a radar screen all day long. That being said, the issue I’m running into is finding a safe, viable way to build the time. I got a job as a Jump Pilot for skydivers, but they want the pilot to fly 10+ hours per day without breaks, for very little pay, in a C182. On top of that, they tried pressuring me to fly in unsafe and borderline illegal conditions, which I refused. Needless to say, I told them to find another pilot, because I won’t risk my life, theirs, nor my career.

More importantly, the biggest issue now is the lack of DPEs to conduct checkrides. I had to wait 2 months for my Commercial ASEL checkride after being ready for the sign-off. I looked into getting the multi add-on (which seems to be a requirement, even if I only want to fly the PC-12), but cannot find a place in the country that has shorter than another 2-month wait for a DPE! I cannot afford to fly and stay checkride proficient for 2-3 months why I wait for an examiner. We have run into a training and certification bottleneck. People have ways to afford pilot training, but due to the shortage of examiners, we cannot get enough pilots certified to even start building time.

I would love some advice and direction from any of you guys.

Good decision to refuse the jump pilot gig, Scott. Ten hours without any breaks as a regular work schedule is definitely unsafe. My 135 job allows me to fly as much as 10 hours per day, but that’s in a two crew environment operating in the flight levels with all the air conditioning and automation we could ever want. There were days when I logged 10 hours at Medfly, but they were very few and far between, and it was also done with two pilots.

Regarding that training bottleneck, the DPEs ranks are filled by flight instructors, so if pilots in general — and experienced CFIs in particular — are lacking, it stands to reason that examiners would be in short supply as well. That’s something the FAA needs to address, and quickly. It’s also causing the existing DPEs to raise their prices. A friend recently paid $1,200 for an initial CFI checkride.

I know several other pilots who have waited 3+ months for an opening in a DPE’s schedule. Have you checked with ATP? They have a large fleet of multi-engine Seminoles, and although I notice that the multi-engine add-on is no longer listed on their web site, they certainly do a lot of multi training. You might also try American Flyers, and Angel City Flyers. They both have a significant number of multi-engine airplanes.

As for the examiner, that’s harder to answer. The only way to know is to call them and ask, but schools which send large number of applicants to the DPE might have better luck getting things scheduled. I’d also check and see if you can schedule the DPE *first*. If your checkride date is 3 months out, the start your training a couple weeks prior. That’ll keep everything fresh and prevent you from spending more money than is necessary just to keep current.

Ron, what are the qualifications? Do FO candidates for such a position need turbine time? Or just appropriate ratings (multi, instrument, commercial)?

It depends on the operator, aircraft type, and account. In this particular example, I believe they required 2500 TT and 1500 multi, 1st class medical, and a valid passport. I don’t recall turbine time itself being a requirement. Keep in mind those are the bare minimum requirements, and I’m going from memory — it’s been a while since the example I cited was active.